“We want to know what peace is – we want to feel it”

In violent conflict, communities are the ones who are the most affected and who experience first-hand any changes brought about by ceasefire agreements.

In violent conflict, communities are the ones who are the most affected and who experience first-hand any changes brought about by ceasefire agreements.

These people need to be heard for a deeper understanding of how ceasefires arrangements, and wider peace processes, affect those at the forefront of the conflict.

Listening to communities

Published by the Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies (CPCS) and produced in collaboration with state-based partner organisations across Myanmar, We Want Genuine Peace: Voices of communities from Myanmar’s ceasefire areas 2015 is based on year-long research and direct engagement with communities in six conflict-affected areas of the country.

Together with other local organisations, the Kayin Development Network, Ta’ang Student & Youth Union, Mon Women’s Organisation, Karuna Myanmar Social Services, Kayah State Peace Monitoring Network and Swe Tha Har Social Services were instrumental in the realisation of the project.

Together with other local organisations, the Kayin Development Network, Ta’ang Student & Youth Union, Mon Women’s Organisation, Karuna Myanmar Social Services, Kayah State Peace Monitoring Network and Swe Tha Har Social Services were instrumental in the realisation of the project.

These partners mobilised ‘listeners‘ for the project, who are familiar with the local situation, cultures, speak the same language, and know how to communicate with community members. Listeners travelled to remote communities to speak with people from Kachin, Karen, Karenni, Shan, Bamar, Mon, Ta’ang, Pa’o, Danu, Intha, Lisu, and Wa communities.

The overall aim of the project is to collate the voices of people across ceasefire areas in Myanmar every year towards influencing policy discussions and informing decision-makers, including negotiators and other key stakeholders in the country’s peace process.

A call for peace

A call for peace

The research revealed that all communities yearn for genuine and sustainable peace.

“We want to know what peace is – we want to feel it,” said a young Ta’ang farmer from northern Shan State.

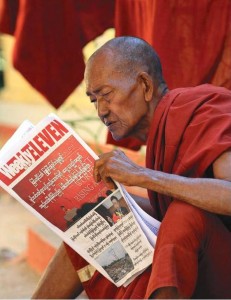

There was a clear desire for the fighting to end and ceasefires to hold, as well as a concerted call for more information about developments in the country’s peace process.

“To implement the peace process, both government and non-state armed groups must come to communities and seek advice and agreement from them. In particular, the leaders and responsible individuals from government and armed groups will have to educate communities about peace,” said a farmer in Kayah State.

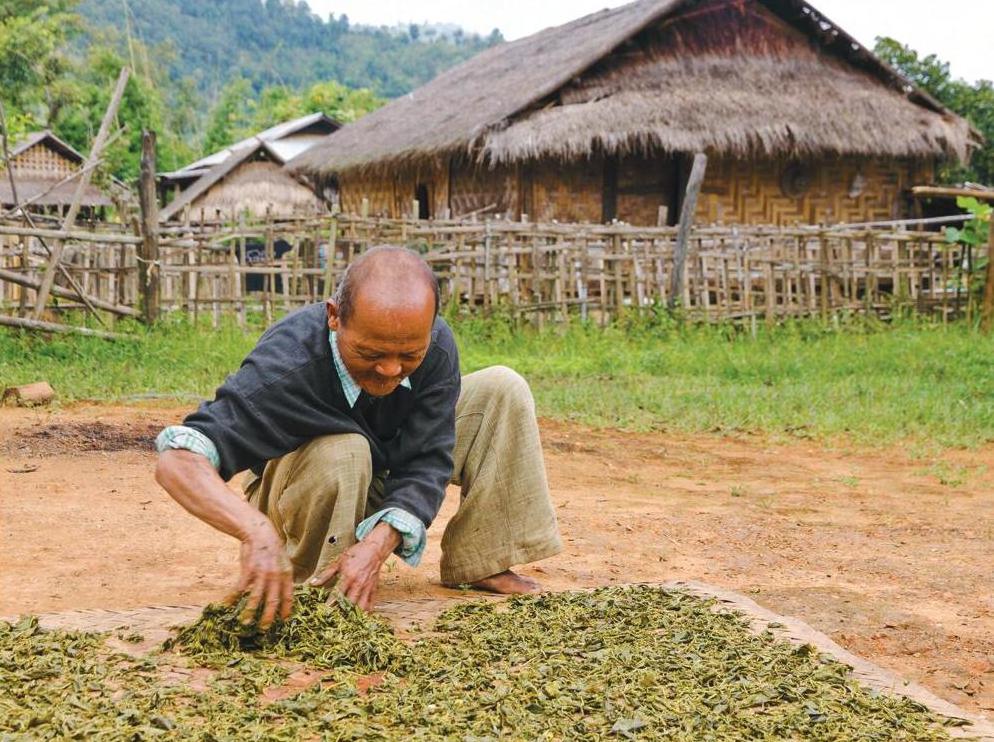

Many communities have lived with the effects of conflict for decades. It permeates every aspect of their lives, from livelihoods, to education and healthcare and social services.

People want to be involved and have their voices heard in policy discussions that shape their lives.

People want to be involved and have their voices heard in policy discussions that shape their lives.

“Peace will come truly if they solve the community’s problems and conflicts as justly as they can after listening to the public, and not by ignoring them. Public participation is really necessary. Public cooperation is very much needed,” said a young Pa’o female from Southern Shan State.

Hopes & fears

Communities highlighted the positive impact bilateral ceasefires have in their areas in terms of freedom of movement, reduced checkpoints, decrease in violent clashes, and infrastructure, although this varied depending on the location of their village.

“The peace process has been good. Before the ceasefire agreement, whenever we went to another village, the military always checked us during the journey because they worried about spies…These days it’s very easy to travel from one place to another,” said an elderly Karen farmer in Kayin State.

“The peace process has been good. Before the ceasefire agreement, whenever we went to another village, the military always checked us during the journey because they worried about spies…These days it’s very easy to travel from one place to another,” said an elderly Karen farmer in Kayin State.

While the positive changes brought about by the ceasefires made many hopeful and optimistic, there is a lingering fear that the ceasefire agreements might be broken, as in the past, and fighting would return to their areas.

“If war breaks out in this region again, children’s education and regional development will be affected. In the future, we don’t want any communal or ethnic conflict. We want equal relationships and mutual respect for each other,” said a middle-aged man from Chipwi, Kachin State.

There is also real anxiety regarding the sustainability of the peace process, and trust is a critical issue. Many said that deeper trust-building between the government and the different ethnic armed groups would improve the possibility for the implementation of agreements.

“…lasting peace requires the government and armed groups to work together and implement the peace process in practice. If they can do so, people will trust both of them,” said a middle-aged Karenni farmer from Kayah.

Unintended consequences

Unintended consequences

A number of communities said drug production, trade and addiction is an issue that needs to be addressed within the wider peace process because they believe it increased significantly in their areas after the ceasefires were signed.

“It is important to resolve the drug issue within the peace process because of the corruption and the lack of genuine efforts to fight the problem. The government should conduct a drug education programme, provide a drug combating system, and supply crops to substitute drug production,” said a middle-aged Karenni farmer in Demoso, Kayah State.

Increased freedom of movement and stability in some areas allowed drugs to be more easily transported and in greater quantities from one part of the country to another.

“Youth become slaves to drugs,” said a university educated young Karenni man in Kayah State.

The drug trade is just one example of unintended consequences if policy makers do not take into account all the possible negative effects that a cessation of conflict can cause.

For more information about the book or to download a copy in English or Burmese, please visit: https://www.centrepeaceconflictstudies.org/publications/browse/10315-2/

“We Want Genuine Peace” will be officially launched in Yangon on June 9. The publication will be available in English and Burmese at the event, which will feature speeches by civil society leaders from conflict-affected areas, local peace practitioners and other distinguished guests. Please contact [email protected] if you would like to attend.